Mathis VL 333

Ernest Charles “Émile” Mathis and His Companies

Émile Mathis was born in 1880 in Strasbourg—now in France, but then in Germany. The Alsace Loraine region, where Strasbourg is located, was part of either France or Germany, depending on which had won the most recent war. He was the son of a successful hotelier in Strasbourg and probably should have thought of himself as German. But his name had a distinct French pronunciation—“mat-EEC,” sounding the same as the famous impressionist painter, Henri Matisse. So the Mathis family probably thought of themselves as French. That may have been what led to several emigrations by Émile, all the result of the major wars of the 20th century.

The main product of Mathis & Co became the Hermes cars, built under license from Bugatti. Unfortunately, they apparently had serious reliability problems. In 1906, when production of the Hermes cars ended after many complaints, Mathis tried to get Bugatti to buy back the remaining chassis and parts. With the failure of the Hermes, the relationship between Mathis and Bugatti soured. Bugatti tried to remove all mention of that relationship from his papers, although the list of Bugatti “types” still shows Type 6 (1904) and 7 (1904-05) as Mathis-Hermes.

Mathis built his first large factory in Strasbourg in 1907. It was in that factory, in 1910, that he built the first “true” Mathis automobile. His first automotive succeses were his Babylette with a 1.1-liter engine and the 1.3-liter engine Baby. The car used a small, multi-cylinder engine probably based on Bugatti’s work.

He continued to be a successful “German” automobile manufacturer until the start of WWI, when, in 1916, he was conscripted into the German army. It appears that the army sent him to Switzerland to buy equipment and supplies for the German government—tires and trucks are mentioned in different references. On what turned out to be the last of these trips, he deserted to France with the German money and joined the French army. He remained away from Strasbourg until the end of the war when he returned to his home and factory, now a part of France once again.

He was soon producing cars again, attracting the attention of other automakers and dabbling in a little racing. In 1921, Spyker, in Holland, imported Mathis voiturettes and called them a Spyker-Mathis. It was an attempt by this upmarket firm to add an economical car to its lineup. This too was a failure, apparently because the Dutch public refused to believe that any car by Spyker was economical. Racing was never a focus for Mathis, and there were few good results to show for the races in which they ran. But they were raced—René Dreyfus drove a 6-hp Mathis in his first amateur race. During the early 1920s, Mathis & Co. entered its cars in the French Grand Prix, but they were serious underdogs, as they were 1.5-liter cars competing in a three-liter formula. In the 1921 French race, the cars started in pairs at 30-second intervals. The first pair away was Mathis in one of his own cars, against DePalma in a three-liter Ballot. Mathis fell back quickly, retiring after 6 of 30 laps. Jimmy Murphy won the race in a Duesenberg.

Despite the lack of racing results, the company grew. Mathis cars were popular. By 1927, Mathis had become the fourth largest manufacturer in France, producing more than 20,000 cars that year. In an attempt to compete with Citroën, Mathis began producing six- and eight-cylinder cars. He was serious enough to engage Italian designer Giuseppe Merosi to consult for the company. Then the Depression intervened, and Mathis had to look for other markets for his cars. One failed attempt was a joint venture with William Crapo Durant in 1930. Durant felt he had missed an opportunity when he was unable to join with Austin for what became the American Bantam. His idea was to produce 100,000 Mathis cars in his Michigan factory. As with so many other plans during the Depression, Durant ran out of money, and the planned venture was scrapped.

Mathis continued to struggle. He built a short-lived FOH with a three-liter, straight-eight engine in 1931 to compete with the bigger French and German cars, and he introduced the Emyhuit with a synchromesh transmission and hydraulic brakes in 1933. All too late—the Mathis factories closed. Then a new opportunity arose in 1934—Ford was looking for a European partner. New tariffs had made it not economical for an American auto company to inport cars into France. Mathis and Ford joined to create Matford SA Française in Strasbourg. The cars copied the style of British Fords and became their major competitor. Eventually, Ford found a way to operate in France without a partner, so Mathis was dropped and production ceased in 1939.

As the Nazi war machine began its march through Europe, it was obvious to Mathis that the Alsace would be in the German sights. He also knew he would be on the German “most wanted” list because of his “desertion” during the “War to End All Wars.” By the time France fell, Mathis was in the United States. Fortuitously, U.S. machine tools he purchased for his factory in France had not yet been delivered, so he kept them in the U.S., created Matam (Mathis-America) and began manufacturing munitions for the U.S. Navy. It is estimated that he built 260 million shells during the war, and in fact received a Navy commendation for his efforts.

At the end of the war, his company was bankrupt—puzzling, since knowing that the war was coming to a close and that munitions would no longer be needed, he could have made plans to begin manufacturing something different; he certainly had the capability. He had built prototypes of a small car for the U.S. market during the war—Dutch Darrin may have even been involved in the design. Unfortunately, the U.S. was not ready for a small car, and either Mathis didn’t recognize another opportunity or wasn’t interested in continuing Matam.

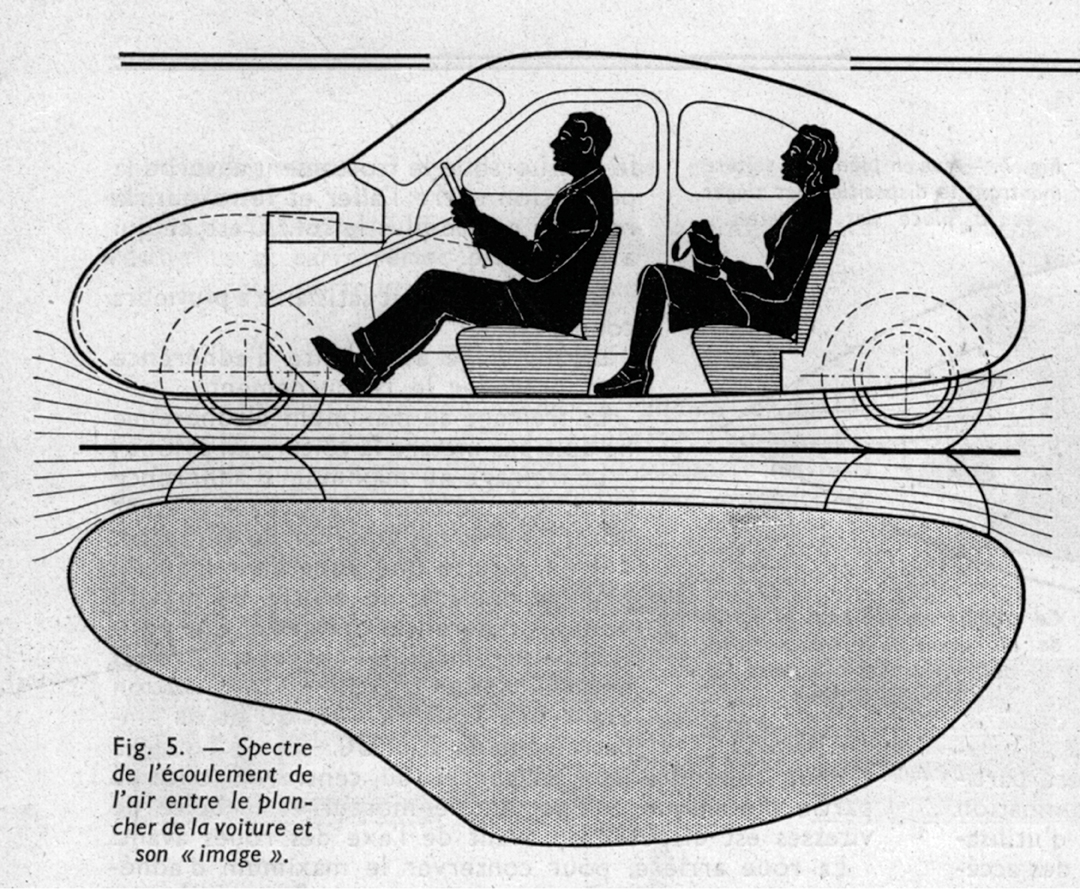

Automobile designers and innovators have tried to find the best aerodynamic shape for their vehicles. Even in the early days of the 20th century, Castagna produced a special bodied Alfa for an Italian count—rounded at the front with the body tapering to a point at the rear. Industrial designer Norman Bel Geddes wrote, in the 1930s, that the teardrop was the ultimate shape for an automobile. R. Buckminster Fuller built three teardrop-shaped Dymaxion cars that he intended to show at the World’s Fair in Chicago in 1933-’34. Other designers had a variety of ideas about how to achieve better aerodynamics other than the teardrop. Some results of their work, like the Martin automobiles in the Lane Motor Museum, were seen as oddities and never put into production. Many other automobiles included aerodynamic elements in their design—the Chrysler Airflow is a good example—but it was rare for a truly aerodynamically designed car to reach mass production.

Production car designers weren’t the only ones seeking aerodynamic efficiencies. A slick skin and low coefficient of drag was especially important to designers of racecars too. Land speed record cars are probably the best examples. From MG to Mercedes-Benz, many manufacturers were looking to use speed records and race wins to help market their cars, but these were cars that had limited application to the production cars of the time. Great for marketing, but they were a bit too far from the shapes that the public wanted on their cars.

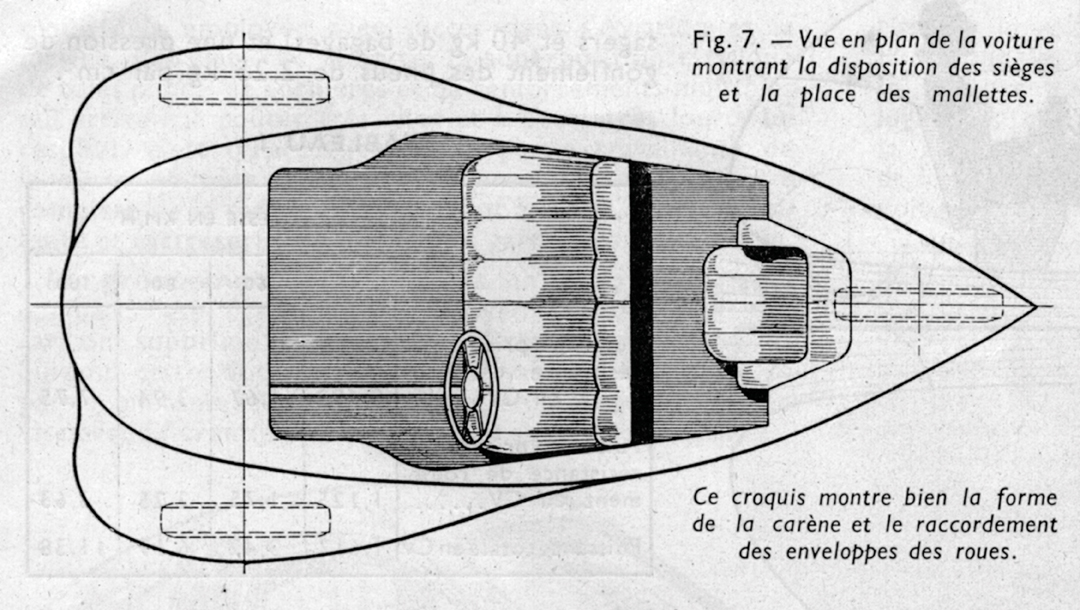

When it came to designing the most aerodynamic automobile, some designers believed that the car should have only three wheels, so the bodywork could taper in a way that would smooth the flow of air over the car’s body. Of those who developed three-wheel designs, most, like Fuller, put the single wheel in the rear. Gary Davis put it in the front apparently to allow four-across seating in his car. His design was successful enough to sell 18 cars, but not successful enough to keep the company in business.

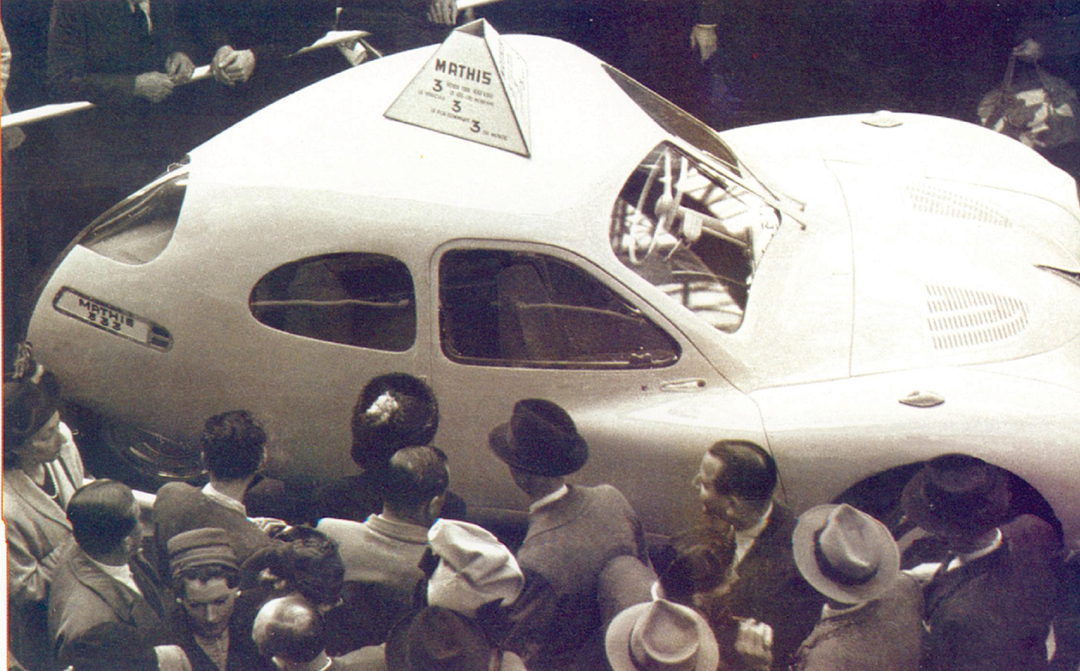

Émile Mathis believed in small, economical automobiles. He sometimes produced big, powerful cars, but he always had small cars in the company’s lineup. Possibly his crowning achievement was his innovative VL 333—three wheels, three passengers, and three liters of gasoline per 100 kilometers. Beginning in 1942, several prototypes were built, but only one, the last one, still exists. The VL 333 was a very innovative automobile in many ways—body shape and construction, suspension, and engine are the most obvious.

Development of the car continued in France during the war despite the firm’s owner being in the U.S. Between 1942 and 1945, nine prototypes were built and tested. This was done secretly since the Germans forbade work on automobiles for the civilian sector. Somehow, the prototypes secretly crossed the border into Switzerland where they were road tested then snuck back into France.

The end of the VL 333 was a shame. It had been acclaimed at the Paris Auto Show in 1946 and widely advertised. It appeared to be a car desperately needed in post-war Europe —small, low cost, and very economical. It was tested by the French government and got 69 miles per gallon, but decisions were made that prevented the manufacture of the car. Mathis tried one other more conventional car, a four-wheel, six passenger, six-cylinder called the 666, but it was also never produced.

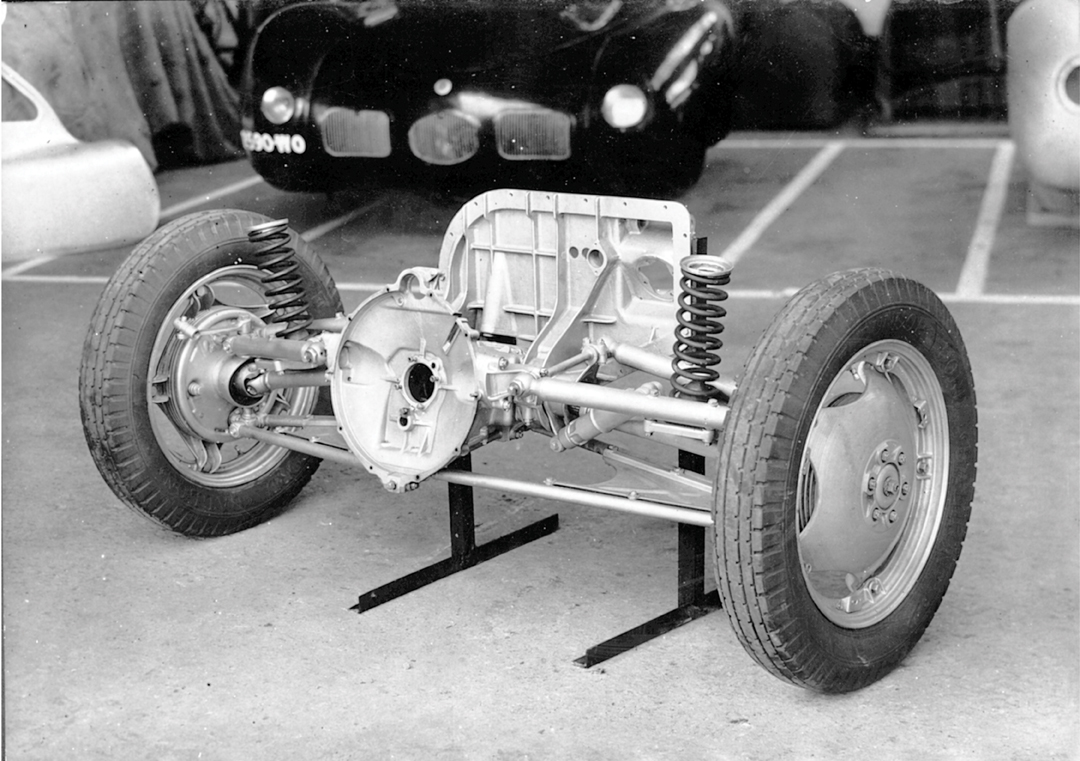

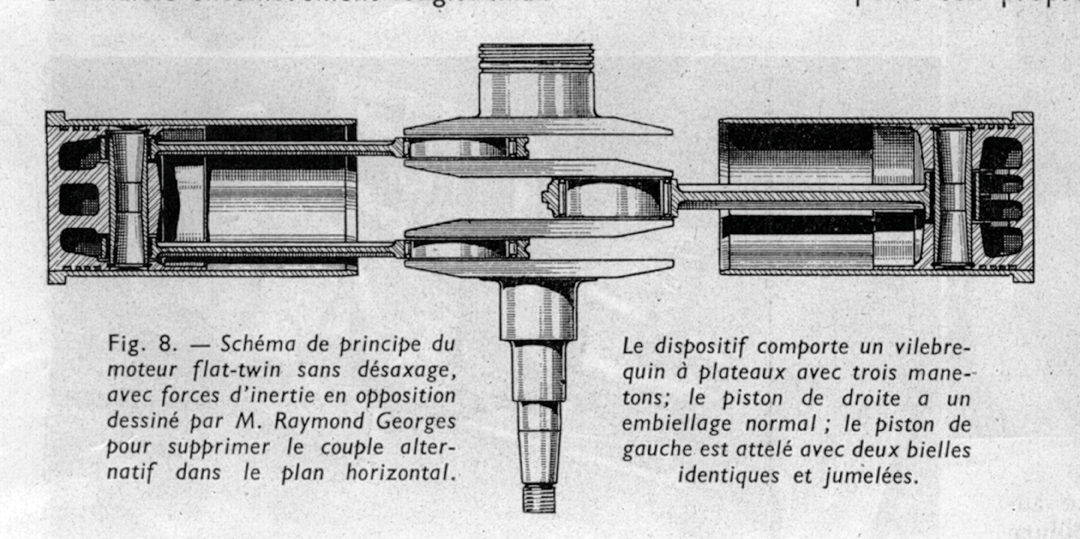

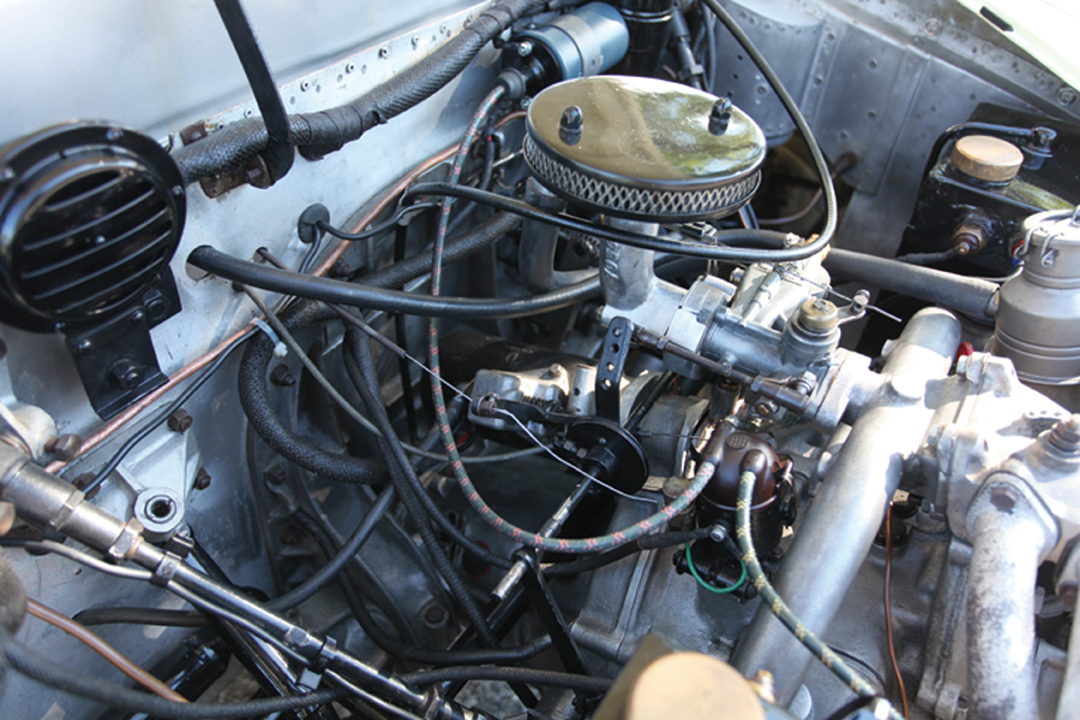

The car has unibody construction, using 20-gauge aluminum sheet metal requiring 6000 spot welds. The engine is a 700-cc, flat twin producing about 15 hp and driving the front wheels through a four-speed transaxle. The engine is unusual in that the pistons and rods are designed so that both pistons’ stroke is out from the crankshaft at the same time and in at the same time, rather than operating like conventional opposed pistons—one going out from the crankshaft while the other is coming back in. It has two separate cooling systems—one for each cylinder—but no water pump. Out of concern for driving the car in Florida, the car was tested in July, but it did not overheat. Still, to be safe, gauges were added to keep the driver informed of engine cylinder temperatures.

Driving Impressions

The use of aluminum kept the weight of the car low – only 850 pounds – and fuel economy high, 69 mpg, as already noted. But with only 15 hp, it is not a fast car. Top speed was once tested to be 105 kmph (65 mph), but acceleration might be best measured in rotations of the Earth. It is a momentum car – a driver does everything possible to keep the speed up at all times. That is important to keep in mind when driving the Mathis, and I did my best to keep the revs up in each gear while negotiating the winding roads of our test drive.

Entry and exit requires some attention to your head, since the slope of the body is such that you can bang your head if you lean back when you enter the car. To start the car, simply turn the key and pull the starter knob. It starts immediately and runs with a bit of vibration caused by the way the pistons move in the engine. The car has an open gate for the shifter —“like a Ferrari,” I say to Andy Kinworthy, the museum’s mechanic. We both laugh at the analogy since there is an important differences—the gate is under the dashboard and out of sight. Kinworthy shows me where to aim the shifter to ensure it goes into first gear —in the center of the right side temperature gauge. In gear, clutch out, and we’re off at a pace that would be politely described as steady. First gear proves to be the only gear difficult to find. Once under way, the shifter falls precisely into each of the remaining gates as long as you keep the revs up. Only when stopped did I have to look to make sure I was aiming the shifter at the center of the right-hand gauge.

With a momentum car, negotiating turns, especially neighborhood corners, requires keeping the speed up. The car has surprisingly little lean, thanks to its wide stance and independent suspension at the front. The seats are comfortable but offer little lateral support, so it’s a good thing that the Mathis is not a fast car in the corners! The steering wheel is large, so steering effort is low. Gauges are positioned so that they’re easily seen.

The brakes are small drums, but they are quite good for this light car. They slow the car smoothly without any grab. Kinworthy tells me that there are reports that if you go fast enough and brake hard enough, the rear wheel will lift off the ground as you stop. I didn’t try it, and I don’t think anyone at the museum has either. The story is believable, since it is very light in the rear—one person can lift it off the ground.

I’ve heard it said by the Top Gear presenters that it is most fun to drive a slow car, fast. I can’t say that I drove the Mathis fast, but it was a fun car to drive—just getting the shifter gates right was satisfying—but it is the level of head turn that the car generates that makes you smile the most. Ludvigsen said the car is “not unattractive;” I’d have to agree with that and add that it is unusual enough to be cool. I am privileged to have been able to drive it.

Epilogue

There are a number of mysteries associated with Émile Mathis and his cars. Why did he allow Matam to fail when he likely could have taken advantage of the demand for consumer goods after WWII? Was it always a ploy by Ford to use Mathis as a way into France with their own cars? Why did the French government refuse to allow Mathis access to the materials he needed for the VL 333? Was it because of the level of effort to manufacture the body—6,000 spot welds? Was there a prejudice against three-wheeled or two-door cars? What happened to all the records Cerf found missing? And where did all the money come from after each failure or bankruptcy?

The last and most mysterious of the questions surrounding Mathis was about the way he died. He was killed in a fall from a hotel window in Geneva in 1956. Was it an accident? Suicide? Murder? No one knows.

Thankfully, one of his best accomplishments remains. The Mathis VL 333 is a window into his vision of the French automobile industry—a vision of innovation not shared by the French government at the time.

Specifications

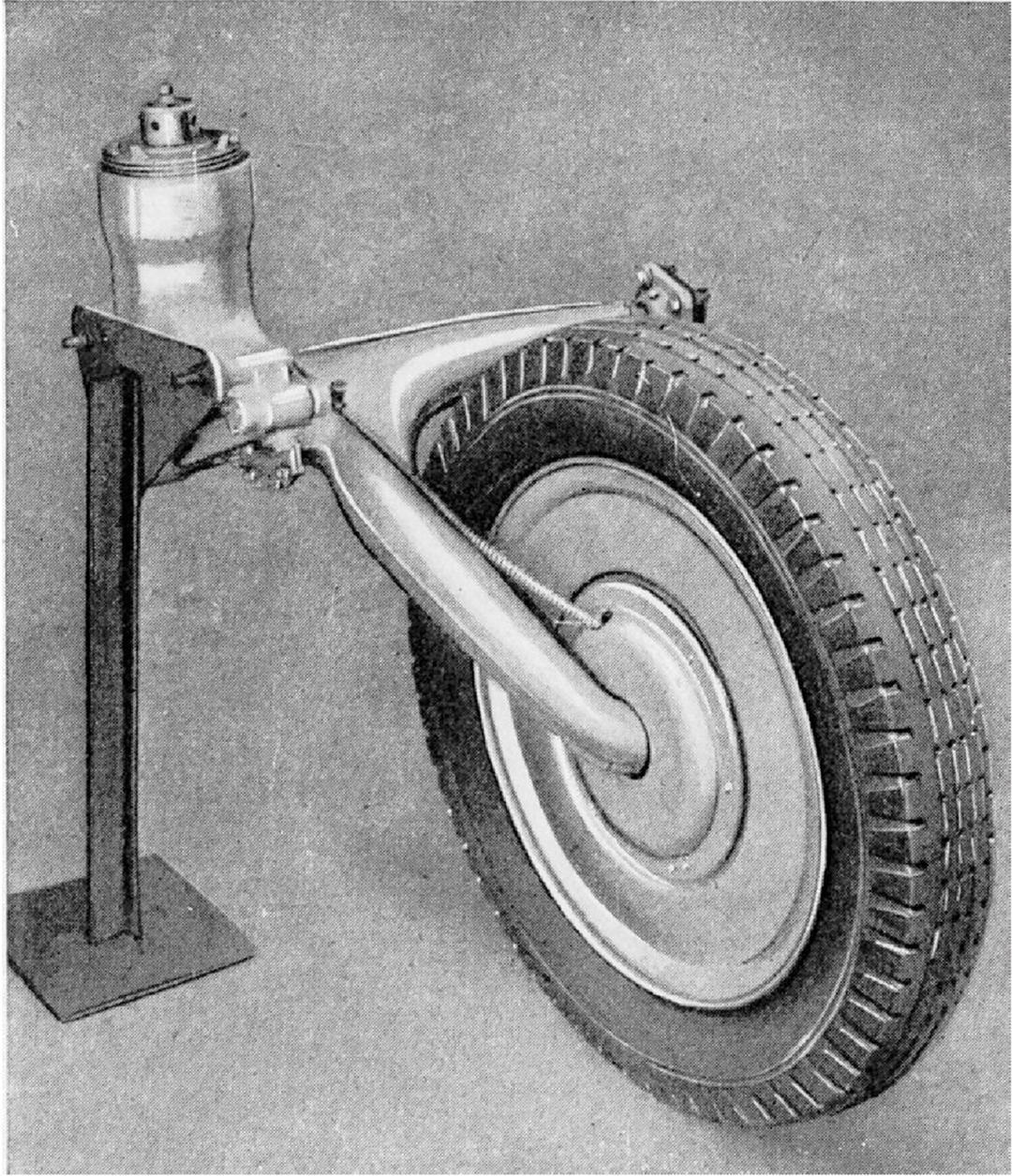

Body: Aluminum unibody fixed-head coupe Wheelbase: 2300mm/90.6 inches Track (front): 1500mm/59.1 inches Length: 3400mm/133.9 inches Width: 1740mm/68.5 inches Height: 1425mm/56.1 inches Weight: 858 pounds Suspension: Independent. Coil springs with separate shocks in front; adjustable hydraulic cylinder with internal spring in rear Engine: Flat two-cylinder Displacement: 707cc/43.144 cid Bore/stroke: 75x80mm/2.95×3.15 in Compression: 6.25:1 Power: 14.85bhp @ 3000rpm Induction: Single downdraft Zenith carburetor Transaxle: Four-speed manual driving the front wheels