The 1950s were a halcyon period for American car manufacturing. After the deprivation of the war years, the American public yearned for a little excess—bigger, faster, flashier. Catering to this new appetite, during the 1950s American manufacturers went through a rapid period of automotive development, both technically and stylistically. On the technical side, the widespread development and use of the V8 engine ushered in a new war—one of ever escalating power, while in the styling department, wartime advances in jet technology and the growing prospect of space travel heralded a new and rapidly evolving automotive aesthetic that saw American cars grow not only bigger, but sleeker and with an ever more outlandish cadre of fins, bullets and other aircraft-inspired flourishes. While all of the major American manufacturers prospered during this decade of flashy excess, one in particular seemed to ride the crest of that wave best—DeSoto. Like most large waves, however, that one came to a crashing conclusion by the end of the decade, and in DeSoto’s case, with devastating consequences.

In the summer of 1928, Walter P. Chrysler announced the creation of a new brand of automobiles to be built under the Chrysler Corporation’s parental umbrella. Earlier in the decade, Chrysler had stepped in to resuscitate the ailing Maxwell-Chalmers brand. By January 1924, Chrysler had rejigged and eponymously renamed the company launching his new brand around a lower priced, 6-cylinder offering that featured a host of new technologies including 4-wheel hydraulic brakes, rubber engine mounts and a new rigid rim wheel design that would go on to become an industry standard.

By 1928, Chrysler looked to extend his company’s success and influence by segmenting his company’s offerings. Chrysler introduced the Plymouth brand of automobiles to serve as a low cost, entry-level vehicle, while the acquisition of the Dodge brand would fill the middle-to-upper bracket, just beneath the premium Chrysler nameplate. This left a slot in the mid-priced market, which Chrysler filled with the creation of another new brand, DeSoto. Named after the 16th century Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto—credited with “discovering” the Mississippi River, though Native Americans may contest that!—the DeSoto brand was created to offer an affordably priced automobile that featured a host of technologies and refinements normally found on much higher-priced vehicles. Like the explorer himself, the DeSoto line would appeal to buyers who traveled a more “adventurous” path, both technologically and stylistically. The new brand’s first offering was the 1929 DeSoto Six Series K, which featured a 175-cu.in., inline, 6-cylinder, L-head engine delivering 55 hp, as well as such advancements as four-wheel hydraulic brakes, automatic windshield wipers, an ignition lock, brake lights and a tool kit as standard features. All this was available, in either a roadster or sedan body style, for just $845. So successful was DeSoto’s initial offering that within the first year more than 81,000 examples were sold and 1,500 dealerships were established, making DeSoto the most successful brand within the Chrysler constellation. In fact, the DeSoto’s first year sales record would remain unbroken for the next 30 years.

Chrysler’s segmentation and market rationalization, in 1928, proved to be prescient, as the Great Depression began to strangle the country in the early 1930s. The ability to sell entry level (Plymouth) and good value (DeSoto) offerings meant that Chrysler fared much better than other manufacturers that couldn’t adapt with the changing times. Throughout the early ’30s, Chrysler continued to invest in new development, but also turned to a number of high profile “publicity stunts” to keep its brands top of mind with the dwindling market of potential car buyers. In 1932, Indy 500 winner Peter DePaolo was hired to speed a DeSoto across the United States in just 10 days. The following year, another Indy racer, Harry Hartz, performed an even more outrageous stunt when he drove a DeSoto across the United States…backward! As crazy as Hartz’s backward trip may have seemed at the time, it actually laid claim to a technological foundation Chrysler would continue to develop in the coming years.

As early as 1927, Chrysler was exploring the new technological frontier of aerodynamics. Whether by accident or intent, Chrysler’s early experimentation discovered that a number of their designs seemed to be more aerodynamically efficient, when tested back to front! This seemingly bizarre aerodynamic discovery led not only to the Hartz backward drive across America, but also to an entirely new take on body design. The ultimate result of this new direction manifested itself in the 1934 debut of the DeSoto Airflow.

The DeSoto Airflow was a radical departure from any other mainstream American automotive offering. Not only did it feature a smoothed and streamlined envelope body with integrated headlights and covered rear wheels, it also boasted a completely new chassis placing the passenger cabin forward a full 20 inches, yielding an automobile with much better weight distribution and handling. On the track, the Airflow broke 32 stock car records, including speed records in the flying mile as well as 100-, 500- and 2,000-mile distances. So efficient was the Airflow that one was raced across the Untied States and averaged a remarkable 21.4 mpg! Interestingly, while it was received with rave reviews in Europe, it appeared to completely overshoot the buying public’s tolerance for change in America. Despite the Airflow’s quantum leap in design and performance, DeSoto’s sales dropped nearly 47 percent, with only 13,940 Airflows being sold in 1934. By 1937, Chrysler acknowledged the Airflow’s lack of sales when it rebodied the car with a more “conventional,” though less efficient body, renaming it the Airstream—sales that year of the rebodied model soared to more than 81,000 units!

In 1938, Chrysler invested more than $15 million in new tools and dies for the next generation of Chrysler products. DeSoto benefitted from this investment first with a line of cars styled to capitalize on the glitz and glamor of “Hollywood” and then, in 1941, with a completely new “Rocket” look for its cars, featuring a lower beltline and a longer, wider body with an elaborate waterfall grill. This year also brought the introduction of the Simplimatic or “Fluid Drive” semi-automatic transmission. With this arrangement there was a low and high gear setting, but once the clutch was used to pull away, a simple lift of the accelerator pedal was all that was needed to shift up into high gear. In all, 85,980 DeSotos were sold that year.

As World War II swept America into conflict, DeSoto’s manufacturing capabilities were repurposed for the production of parts for Sherman tanks and airplane fuselages. After the cessation of hostilities, it took some time for DeSoto to get fully back up to manufacturing speed and develop new production designs.

By 1950, DeSoto was fully back on its game and introducing totally redesigned models. These new models, like the top of the line Sportsman, were among the largest vehicles within the mid-price category, larger in size than any of the equivalent offerings from Buick, Packard, Pontiac or Mercury. The premium Sportsman model featured a pillar-less hardtop configuration, with wraparound rear windshield and a luxurious interior. DeSoto sales reached an all-time high of 133,854 units.

As the 1950s began to unfold, DeSoto’s tried and true inline, 6-cylinder engine quickly fell victim to the growing horsepower war being waged in the American marketplace. Buyers were increasingly gravitating toward the more powerful V8 engines being offered by manufacturers like Cadillac and Oldsmobile. DeSoto eventually had to respond to this arms race with its own V8, which came in the form of the Firedome Hemi, in 1952. Producing the best yield of any V8 of the time, the Firedome’s 276-cu.in., hemispherical head V8 produced an impressive 160 hp, with just a single two-barrel carburetor sipping regular gas. Despite this class leading power plant, sales of the new Firedome and Firepower models began to diminish relative to their competitors. DeSoto now had the horsepower, but what it needed was advanced styling to match.

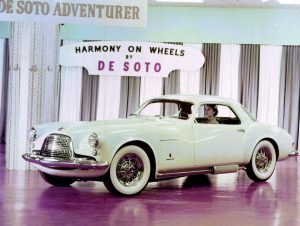

In 1949, Chrysler hired a young designer named Virgil Exner. Exner had served as Chief Designer at Pontiac in the late ’30s and went on to work under famed designer Raymond Loewy on a number of Studebaker designs before a falling out with Loewy in 1944 led him to move directly to Studebaker. However, lingering issues with Loewy and his ties to Studebaker ultimately meant Exner moved to Chrysler’s Advanced Styling Group, in 1949. When Exner arrived at Chrysler, by and large, the company’s cars were designed by engineers, rather than stylists/designers. By 1952, Exner had become Director of Advanced Styling for Chrysler and had lobbied hard to wrestle design control away from the engineers. That same year, Exner began work on a new concept car for DeSoto that he named the Adventurer I. According to his son, Virgil M. Exner Jr., “Father actually started the design at our home in Birmingham, Michigan, with scale drawings and then modeled the ¼-scale adaptation in clay, in his office ‘back room’ along with one of his favorite modelers, Ron Martin. Ron was the son of my father’s clay modeler at GM Styling, George Martin, when father was the Chief Designer of Pontiac from 1936 through 1938. Ron also brought the first use of fiberglass casting to Chrysler Styling, and the Adventurer model was the first to be cast in fiberglass and shipped to Ghia, in Italy, for the full size show car to be developed. Prior to that the scale models were cast in plaster and always subject to cracking of the beautiful finishes.

“The DeSoto Adventurer I was a sporty coupe on a ’52 DeSoto chassis shortened to a 111-inch wheelbase that utilized a 170 hp, 273-cu.in. Powerdome Hemi engine with a three-speed Fluid-Drive transmission. It was a very clean and simple design, one of father’s best of all time.”

The Adventurer I went a long way toward changing the public’s perception of DeSoto as stodgy and boxy. However, by 1955, Exner would move the needle even farther when he initiated a complete restyling of the entire DeSoto line, under DeSoto’s new “Styled for Tomorrow” program. Exner’s new DeSotos were sleeker, lower, wider and visually appeared more aerodynamic. New versions of the Fireflite and the Firedome not only sported this new updated design, but also benefitted from DeSoto’s first wraparound windshield, two- and three-tone paint schemes with styled color “speed strakes” dressing side profiles and a Poweflite automatic transmission. The new designs were an instant hit, with 114,765 vehicles being sold in 1955 alone.

A lot was to change in 1956. At Chrysler, Exner was to reveal the first of what would come to be known as his “Forward Look” designs, which for DeSoto yielded even lower, wider and sleeker vehicles that—in a nod to aerodynamics and the burgeoning jet age—would eventually sprout pronounced tail fins. Looking to go after the more performance-minded buyer, DeSoto released a new high-performance, two-door model named, the Adventurer. Packing a 341.4-cu.in Hemi V8, boasting 320 hp, the new Adventurer proved its mettle by making a 137 mph speed run at Daytona Beach and followed up by clocking 144 mph on the banked oval at Chrysler’s Chelsea Proving Grounds. Added performance appearances in 1956 included serving as the pace car for both the Pikes Peak Hill Climb and that year’s Indianapolis 500.

For 1957, Exner again restyled the entire DeSoto lineup with an even more “Space-age”-inspired look. Tail fins were now even larger and more pronounced, in theory to provide more high-speed stability to the ever-faster lineup. Other space-age touches included dual exhaust ports and protruding bullet taillights that gave the DeSoto the look of a jet engine with its afterburners on.

In 1957, the top-of-the-line Adventurer received an upgraded Hemi engine that, for the first time in a standard configuration American car, yielded one hp per cubic inch of displacement—345 hp from a 345-cu.in. engine. Rounding out the package was a new three-speed TorqueFlite pushbutton automatic transmission, Torsion-aire torsion bar suspension and, for the first time, the availability of a convertible Adventurer. While Buick, Oldsmobile and Pontiac sales plummeted in 1957, DeSoto’s went up to 117,514.

Beginning of the End

While 1957 was a peak year for DeSoto in terms of sales, at the same time it was also perhaps its nadir in terms of quality control. DeSotos built in the company’s Los Angeles plant were reportedly so poorly constructed that when it rained their interiors would literally fill full of water! This, combined with rust problems, overall poor reliability and Chrysler-wide quality issues badly hurt DeSoto sales in 1958.

DeSoto tried, in part, to address its quality issues in 1958, with the introduction of a lighter weight, less complicated replacement for the Hemi, the 361-cu.in. Wedge-head V8. However, the ’57 quality problems were further compounded when DeSoto made the tragic decision of offering the 1958 Adventurer with the first electronic fuel injection system (Bendix) available on a production car. Both expensive and temperamental, the few cars that came so equipped had so many problems that they were soon recalled and retrofitted with dual 4-barrel carburetors. While the new Adventurer, with the carbureted Wedge engine was a fine vehicle, the damage to DeSoto’s reputation was done and sales that year plummeted by 70 percent.

The 1958 Adventurer

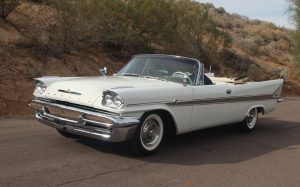

After its introduction and record sales in 1956, the Adventurer received a fairly radical makeover for 1957. With Exner’s “Forward Look” styling fully in motion at DeSoto, the Adventurer sprouted tail fins and side strakes that made the enormous car look like it was about to take flight. Now offered as either a hardtop or convertible, the Adventurer came fully loaded with power (345 hp) and features, but could only be had in black, white or gold paint, with contrasting panels. All told, 1,950 Adventurers were constructed in 1957.

With an economic recession starting to strangle the American marketplace, the 1958 DeSoto Adventurer’s styling remained the same, with only subtle changes including a revised grill and contrasting “speed” strakes running the length of the car. However, the biggest change was under the hood, where the Hemi engine had been replaced with the lighter 361-cu.in. Wedge-head engine that was now capable of hurtling the behemoth to a then unprecedented top speed of 140 mph! As in previous years, the ’58 Adventurer was only offered in black, white or gold colors, but unlike the previous years, only 350 hardtops and just 85 convertibles were constructed. This makes the ’58 convertible tested here, a very rare example indeed. As a result, the car featured here is perhaps the most desirable of a trifecta of Adventurers being sold by Barrett-Jackson, at their 45th anniversary Scottsdale auction, January 23-31. The middle child between a 1957 and a 1959, this 1958 is the rarest among the rare, because so few convertibles were manufactured that year.

Walking around the DeSoto takes time—this is a big car!—at over 221 inches in length and over 78 inches in width, with a curb weight of 4,350 pounds, this has to rank as the largest passenger car I have ever driven. Taking the car in, as it sits in the Arizona desert sun, my eyes are drawn to various components and details—the long speed strake down the side, the tail fins, the wraparound windshield, the enormous tail fins, the quad headlights and jet intake-like front bumper…those enormous tail fins! Visually, it is nearly impossible to look at this car, from any perspective, and not have your eyes swept rearward, up and over those tail fins. Exner loved them for their visual appeal, but also believed in their functionality. His team wind tunnel tested their tail fin designs and—like those on an aircraft—found that they did in fact provide an added level of vehicle stability at speed. And lest one thinks that these were purely for show, keep in mind, this was one of the very few American cars in the 1950s capable of 140 mph…with four passengers, the top down and the optional Highway HiFi phonograph playing in the background!

Grab the key to the right in the rectangular binnacle, give it a twist and the 361 Wedge burbles to life and lays right down into a quiet idle. After placing your foot on the overly wide power brake pedal in the center of the floor beneath you, its time to put the Adventurer into gear…but this is the future, we don’t stir a lever like we used to in “them olden days” now everything we need is available at the touch of a button! Looking just to the left of the steering wheel, nestled up against the A-pillar is a small bank of push buttons, like those you would use to change the stations on your AM radio. With R, N and D, positioned above 1 and 2, I push in the “D” button, lift off the brake, press on the gas and my adventure in the Adventurer is under way.

Despite weighing well over two tons, the DeSoto pulls smartly away, without the appearance of too much effort. The torsion bar suspension gives the car a very smooth, fluid-like ride. At speed, this “fluidness” produces a certain vague, “floaty” feeling, but when assessed in the context of its contemporaries, this was considered the ideal for its day.

Of course, if you’re hurtling a 4,350-pound, land-based spacecraft along at 100-130 mph, brakes at some point in time may become of interest to you. Fortunately, the Adventurer’s 12-inch, power-assisted drums seem to have more than enough gripping strength to haul this Mid-century marvel back down to earth with confidence.

Like so many stories spanning the history of the automobile, it only took the confluence of one or two events to quickly pull the DeSoto brand under the waves forever. While some have since labeled Exner’s “Forward Look” outlandish or excessive, it was exceedingly popular for its day and, but for one year of bad build quality and an ailing economy, it would have been interesting to see where Exner would have taken the DeSoto brand in the 1960s. Sadly, this is a question that will forever go unanswered, leaving the Adventurers of the late 1950s as one of Exner’s and DeSoto’s crowning achievements.