1955 Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR

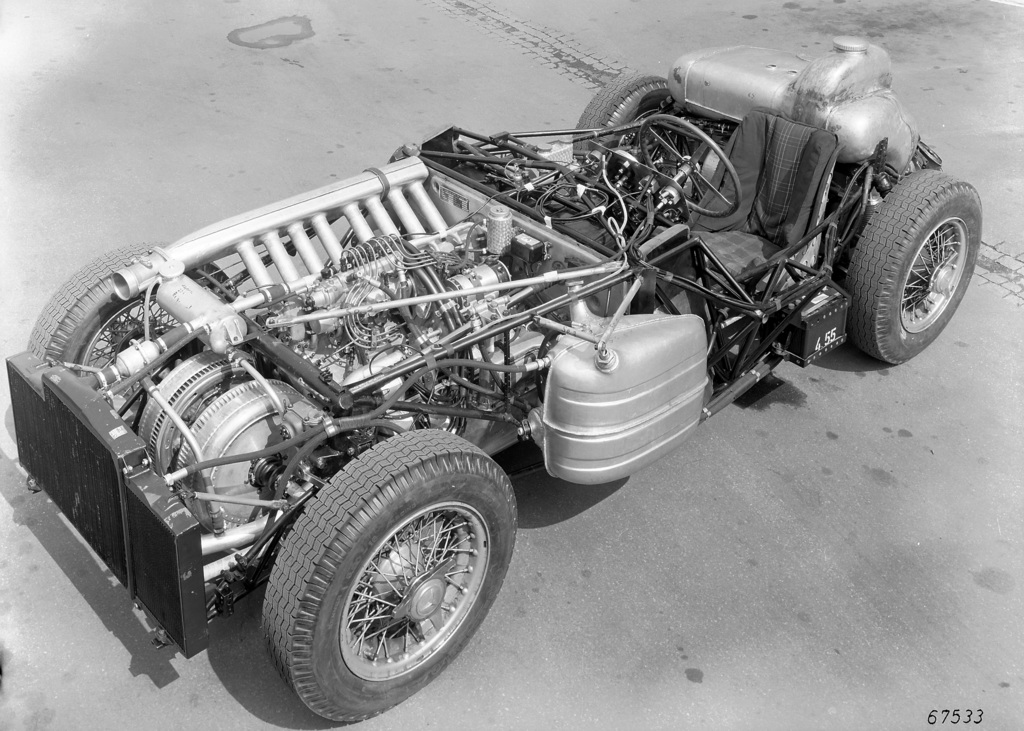

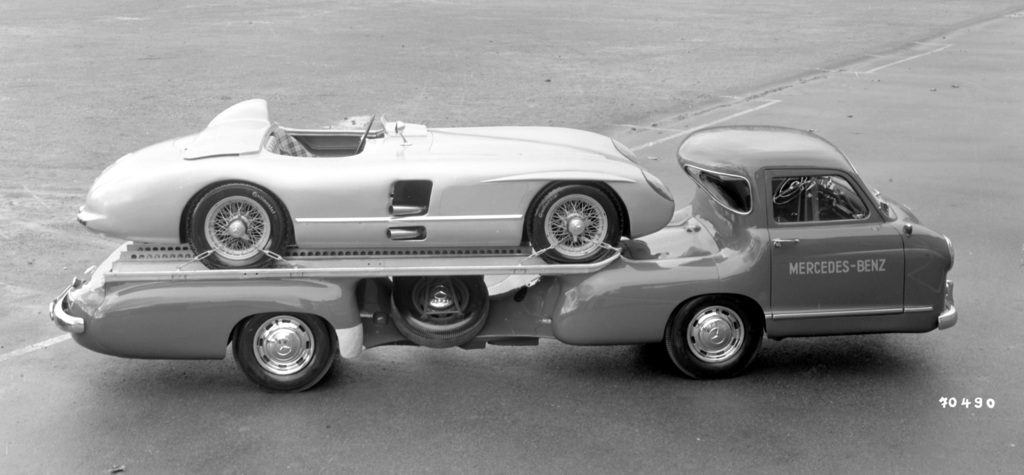

The development of the 300 SLR racing sports car was heavily influenced by the Mercedes 300 SL with striking gullwing doors, which first lined up at the start of the Mille Miglia in 1952 and a road-going version of which made its debut in February 1954. It was this famous model which provided the basic concept for the new racer, featuring a lightweight but high-strength tubular steel frame supporting an aluminium body. However, the 300 SLR also stood out with a host of individual characteristics very much its own. These included a five-speed transmission, 16-inch wheels and larger brakes.

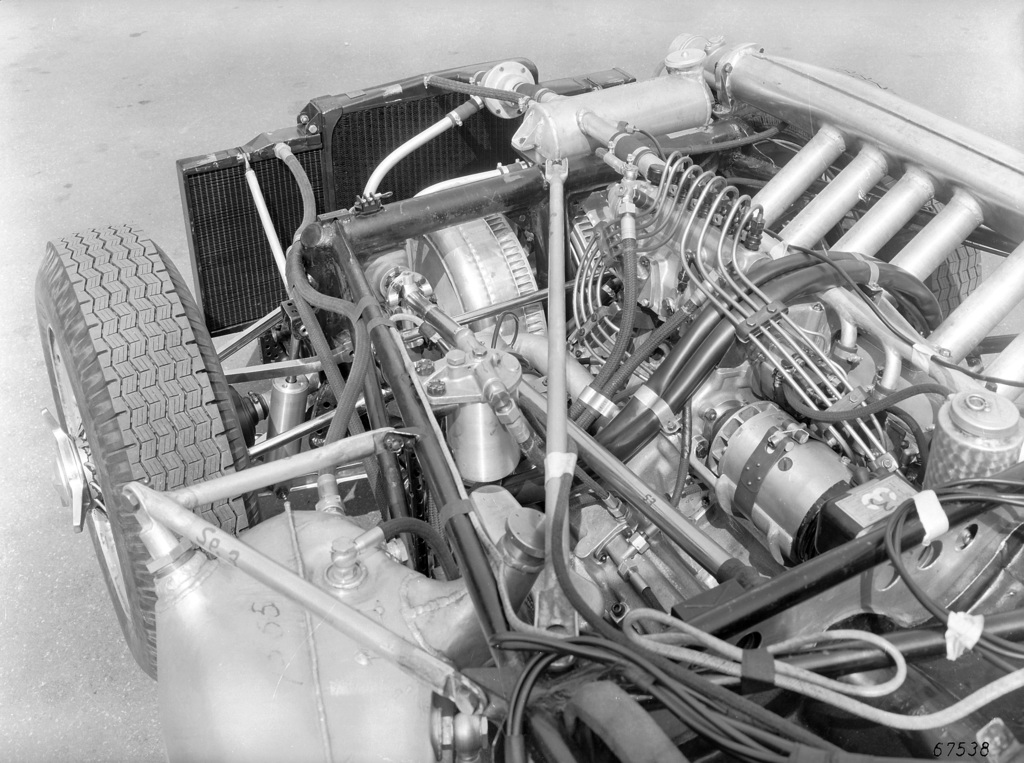

Above all, though, the racing sports car developed far greater output than its ‘little brother’ the SL – an eight-cylinder engine with petrol direct injection and dual ignition, essentially the same unit which powered the 1954 Formula 1 racing car, saw to that. The Monoposto and Stromlinie open-top body variants of the W 196 R Silver Arrow had chalked up numerous victories in international events, including the French Grand Prix, the Nürburgring race, the Italian Grand Prix, the Avus race in Berlin and the Argentinean Grand Prix.

The displacement of the Formula 1 eight-cylinder power unit was increased from 2.5 litres to 3.0 litres for use in the 300 SLR racing sports car. This boosted out-put to as much as 310 hp at 7400 rpm, depending on the intake manifold. Maximum torque of 317 Newtonmetres at 5950 rpm ensured quite majestic pulling power. The hugely powerful engine was mounted longitudinally in the front section of the car at an angle of 33 degrees and supplied with a high-octane fuel mixture of low-lead petrol (65 percent) and benzol (35 percent). In some races, alcohol was also used to push performance up to even greater heights. As a rule, the racing sports car roared off the starting line with 167 litres of fuel and 35 litres of oil on board. However, Moss and Jenkinson began their assault on the 1955 Mille Miglia with as much as 265 litres of fuel in the tank.

Preparation

The Stuttgart-based engineers organised a series of uncompromising test runs in order to establish the durability of the eight-cylinder unit. It was put through its paces over a distance of more than 10,000 kilometres at race speed, before being subjected to a 32-hour non-stop test rig examination. These were merciless tests of endurance, but they were still not enough to break the W 196 S engine.

This exhaustive and extremely intensive programme of testing was a key element in the preparation for endurance road races such as the Mille Miglia, Tourist Trophy and Targa Florio, where the reliability and durability of the materials was an even more important factor than raw speed. The empirical values gained from pre-season testing paid dividends for the Mercedes team and helped earn the 300 SLR a formidable reputation: the Silver Arrows engine, chassis and bodywork proved virtually indestructible.

Rudolf Uhlenhaut

Behind the development of the 300 SL between 1951 and 1954 and the construction of the successful 300 SLR racing sports car was the inspiration of a man who was to become known as the technical brains behind the Silver Arrows: Rudolf Uhlenhaut.

Born in London on July 15, 1906 and the son of a German banker, Uhlenhaut grew up in a multilingual environment. He began his career in 1931 in the testing department at Daimler-Benz, becoming technical director of the racing department in 1936 and rising to senior engineer and head of passenger-car testing in 1949.

Uhlenhaut was an engineer with petrol in his blood, but was also a skilled driver. For example, during chassis testing with the Formula 1 racing car at Hockenheim in 1954, he bettered Fangios best time by 3.5 seconds. However, he never really considered driving in the races himself, instead preferring to direct operations behind the scenes. In addition to his specialist expertise, Uhlenhaut was frequently called on to display a well-honed talent for improvisation. Once such instance occurred during the 1952 Carrera Panamericana. With Mercedes driver John Cooper Fitch complaining that excessive force was required to brake effectively in his 300 SL, Uhlenhaut got down on his hands and knees underneath a service truck, plucked out its brake force booster and promptly fitted it into the SL. Fitch was a happy man again.

Development

When the decision was made mid-way through 1951 to build a new Mercedes road-going sports car, Rudolf Uhlenhaut was there to give the project – known by the abbreviation SL (Sport Light) – the necessary impetus. His was the engineering mind behind the space frame, made by welding together filigreed steel profiles, which supported the engine, transmission and axles. In the development of the frame, he drew on the knowledge gained in the design of a tried-and-tested invention which has itself acted as a kind of supporting framework through the history of motor racing. In the immediate post-war period Uhlenhaut, who had previously played a major role in the success of the Silver Arrows between 1937 and 1939, designed a series of smaller racing cars with rear-mounted engines in which he incorporated a wide tubular frame, the central section of which formed a high-strength triangular construction in front of the cockpit.

This construction was all very well, but it presented Uhlenhaut’s team of engineers with a new kind of problem. The three-dimensional tubular steel frame required more room underneath the doors than earlier constructions, which meant that the doorways had to be moved further up. This ruled out the use of conventional doors. However, in a peerless example of necessity proving to be the mother of invention, the team fixed the hinges to the roof, allowing the doors to open upwards instead of to the side. The legendary gullwings were born.

Rudolf Uhlenhaut returned to this trusted frame concept in the design of the 300 SLR, as it had proved to be not only stable and secure, but also extremely light. The 1955 Mille Miglia version of the SLR tipped the scales at around 900 kilograms, with the engine alone accounting for 234 kilograms of the total weight but the tubular steel frame weighing just 50 kilograms.

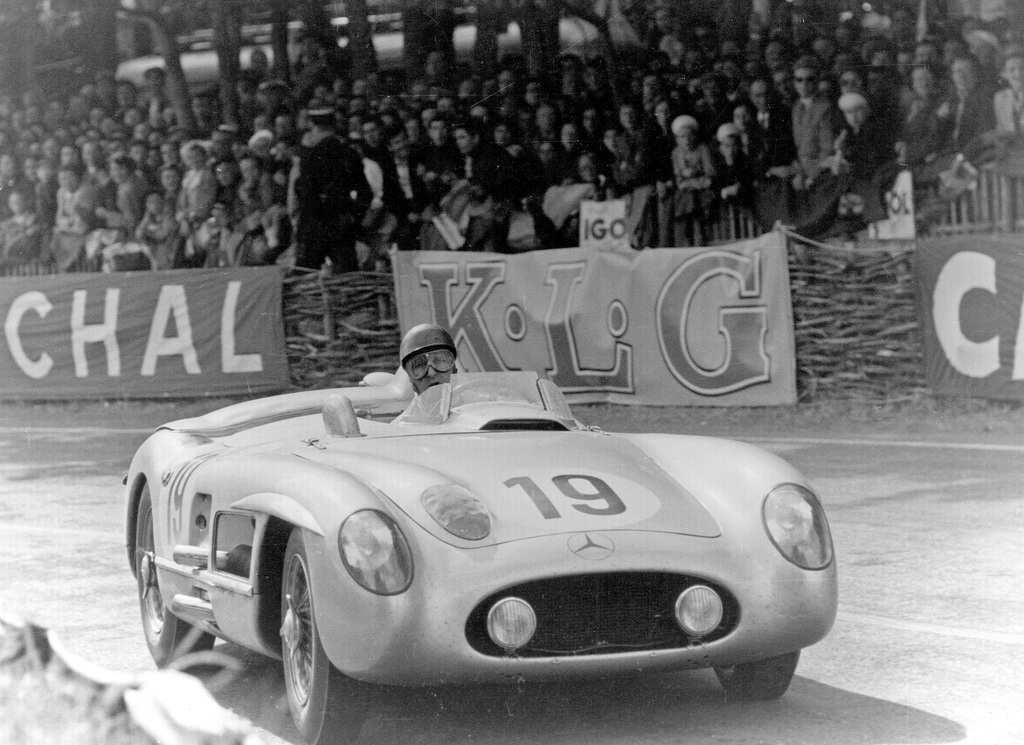

An Air Brake

On the flip side, special braking systems were also on the development schedule. In addition to an anti-lock braking aid designed for emergency situations which worked by injecting oil onto the surface of the brakes – and the hydraulic brake booster, Mercedes-Benz started the Le Mans 24-hour race in June 1955 with an ingenious piece of technology in tow. An air brake fitted to the rear of the 300 SLR could be raised using a hydraulic pump. With a surface area of 0.7 square metres, the light-alloy wing had a significant braking effect as well as enhancing the car’s handling around corners.

The idea for this wind brake was dreamt up by director of motorsport Alfred Neubauer, who was looking to develop an assistance system to help take the strain off the wheel brakes and tyres during endurance tests such as the races at Le Mans and Reims. Neubauer wanted to use the decelerating properties of the cars aerodynamics at Le Mans in particular, as the French track forced the drivers hard onto the brakes lap after lap in order to bring the car down from its maximum speed to as little as 40 km/h.

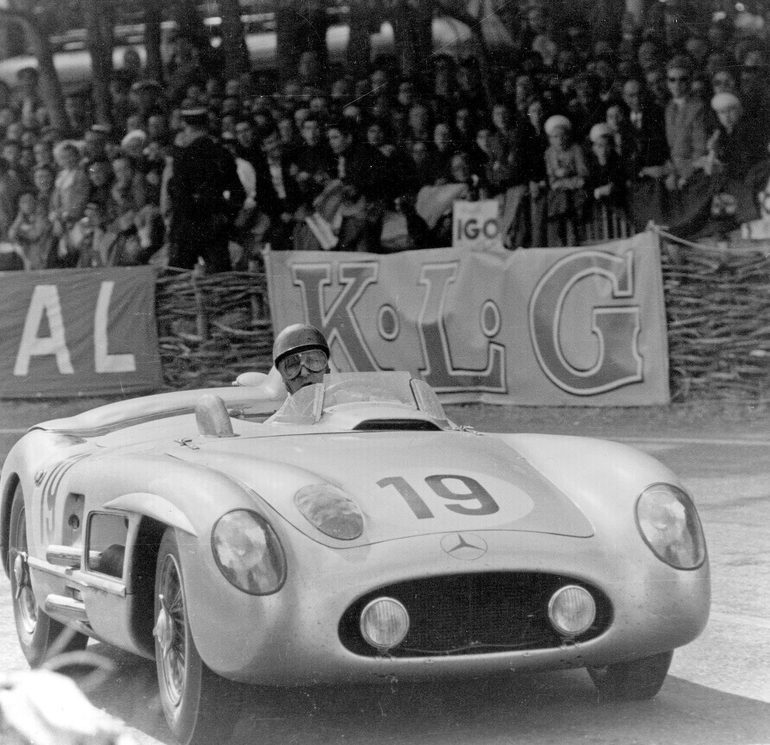

1955 Mille Miglia

Brescia, early May 1955, and on the Piazza della Vittoria at the heart of the north-ern Italian city the cars engines are getting warmed up. Only a few minutes re-main until the start of the 22nd Mille Miglia, the legendary road race which takes the drivers from Brescia to Rome and back again. A total of 533 cars have en-tered the race, a punishing 1600-kilometre endurance test for man and machine alike. Since the competitors set off one by one at intervals, the starting procedure took a while to complete: ten and a half hours to be precise.

It was not until early morning on May 1 when the new Silver Arrows from Stuttgart-Untertürkheim finally left the starting line. Juan Manuel Fangio, Stirling Moss, Karl Kling and Hans Herrmann were the men at the wheel of the four Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR racing sports cars, which were celebrating their debut outing in Italy. ‘This will be a record-breaking race,’ predicted Mercedes director of motorsport Alfred Neubauer. And 25-year-old Stirling Moss, in his first season with Mercedes-Benz, shouted determinedly ‘I’ll win!’

Both were proved correct. In the first section of the race between Brescia and Verona, Hans Herrmann set an average speed of 192.23 km/h. However, by the intermediate station in Rome Stirling Moss had taken the lead.

The 300 SLR with car number 722 duly reeled off the final kilometres up to the finish line to win the 1000-mile race in a record time of ten hours, seven minutes and 48 seconds. With an average speed of 157.65 km/h, Stirling Moss and co-driver Denis Jenkinson had driven the fastest Mille Miglia of all time. Juan Manuel Fangio came home in second place.

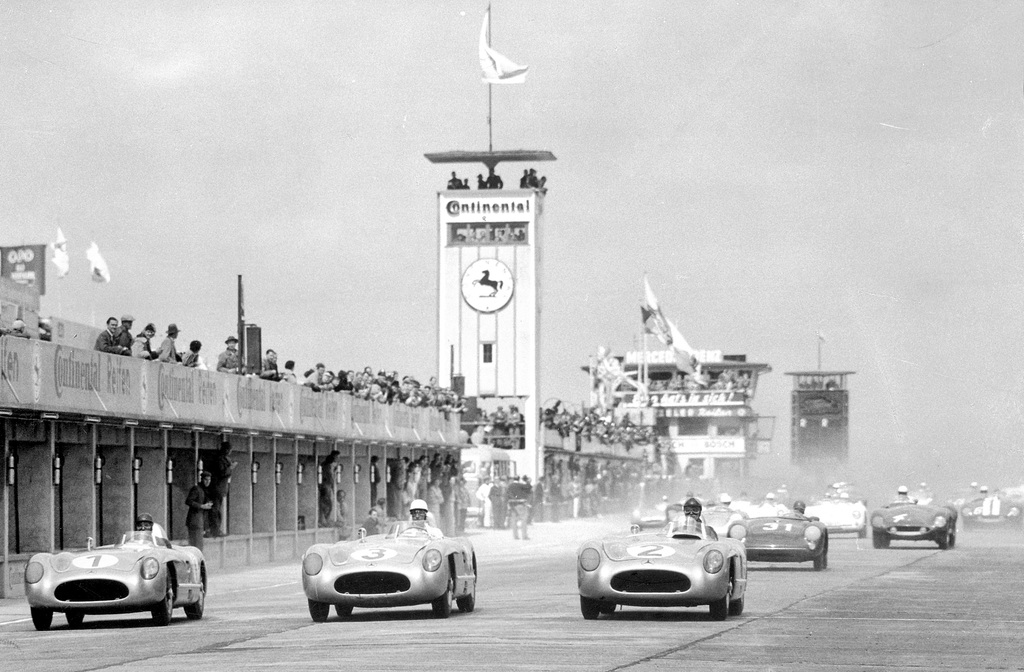

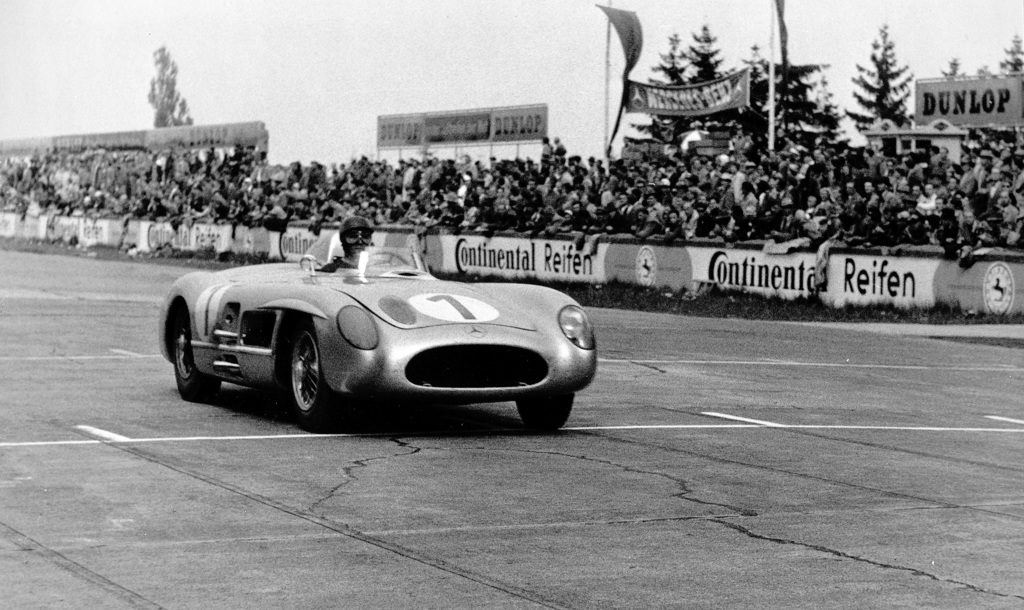

Mercedes-Benz and the new 300 SLR had claimed a magnificent one-two victory and announced its arrival on the motorsport scene in some style. At the end of May, barely four weeks later, the SLR pulled off another one-two in the Eifelrennen race on the Nürburgring. On this occasion Fangio took the honours, with Moss following him home. The 300 SLR went on to become the most successful racing sports car in 1955.

Mercedes-Benz enjoyed incredible success in 1955, but the brand’s winning run was overshadowed mid-way through the season by a tragic accident during the Le Mans 24-hour race. Forced off the track as it approached the pit lane, one of the 300 SLR racing sports cars was unable to stop and careered into a spectator grandstand. In all, 81 people were killed in what was an appalling disaster. Mercedes-Benz immediately called all its cars into the pits and retired them from the race.

Story by DaimlerChrysler, Edited by Supercars.net

In Detail

| tags | 300slr |

| submitted by | Richard Owen |

| production | 2 |

| engine | Type M 196 S, Twin Spark Inline-8 w/Dry Sump Lubrication |

| position | Front Llongitudinal, 53 Degree Inclination To The Right |

| aspiration | Natural |

| valvetrain | DOHC, 2 Valves per Cyl w/Desmodromic Valve Gear |

| fuel feed | Mechanically Controlled Petrol Direct Injection |

| displacement | 2982 cc / 182.0 in³ |

| bore | 78 mm / 3.07 in |

| stroke | 78 mm / 3.07 in |

| compression | 9.0:1 |

| power | 231.2 kw / 310 bhp @ 7400 rpm |

| specific output | 103.96 bhp per litre |

| bhp/weight | 344.44 bhp per tonne |

| torque | 317 nm / 233.8 ft lbs @ 5950 rpm |

| redline | 7800 |

| body / frame | Aluminum over Steel Tubular Space Frame |

| driven wheels | RWD |

| front tires | 6.00×16 |

| rear tires | 7.00×16 |

| front brakes | Inboard Duplex Drum Brakes w/Power Assist |

| rear brakes | Inboard Duplex Drum Brakes w/Power Assist |

| steering | Worm & Sector |

| f suspension | Double Wishbones w/Torsion Bar Springs, Telescopic Shock Absrobers, |

| r suspension | Swing Axles w/Longitudinal Torsion Bar Springs, Telescopic Shock Absrobers |

| curb weight | 900 kg / 1984 lbs |

| wheelbase | 2370 mm / 93.3 in |

| front track | 1330 mm / 52.4 in |

| rear track | 1380 mm / 54.3 in |

| length | 4300 mm / 169.3 in |

| width | 1740 mm / 68.5 in |

| height | 1100 mm / 43.3 in |

| transmission | Rear Mounted 5-Speed Manual |

| gear ratios | 2.67:1, 1.75:1, 1.43:1, 1.07:1, 0.83:1 |

| final drive | 2.222:1 |

| top speed | ~300 kph / 186.4 mph |