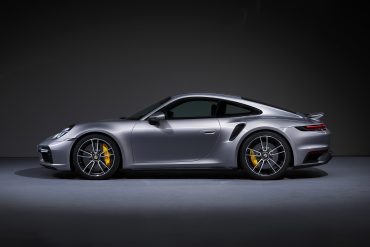

Porsche continues to evolve its iconic 911 lineup with the introduction of three new all-wheel drive models for the 2026 model year: the 911 Carrera 4S Coupe, 911 Carrera 4S Cabriolet, and the 911 Targa 4S....

Ferrari has unveiled the Amalfi, a front-mid-engine V8 2+ coupé that replaces...

Ferrari has unveiled the Amalfi, the long-anticipated successor to the Roma and...

A true successor to the legendary F1, the 2020 McLaren Speedtail pushes...

The Rimac Nevera R is the world’s fastest-accelerating road car. It rockets...

Become a member and unlock exclusive access to member-only content, a totally ad-free experience and be part of a vibrant community dedicated to the iconic enthusiast performance cars.

Latest News & Updates

Only the coolest performance, supercar and collector car news

Lamborghini has added a historic milestone to its motorsport legacy by securing its first overall win at the 24 Hours of Spa. Building on previous endurance racing success—including three consecutive...

Nothing less than perfection: that is what is demanded of each example of the Bugatti W16 Mistral¹ before it is delivered to its owner, undergoing an exhaustive and uncompromising quality...

The Koenigsegg Sadair’s Spear is the Swedish hypercar maker’s most extreme track-focused machine yet — and yes, it’s still road-legal. Based on the Jesko, the Sadair’s Spear is lighter, more...

The Hennessey Venom F5 is a hypercar engineered for extreme performance and named after the highest rating on the Fujita tornado scale. Powered by Hennessey’s proprietary 6.6-liter twin-turbocharged V8, nicknamed...

Highlights The hypercar of the 2000s can be seen at the Mercedes-Benz Museum for the first time – as part of the special “Youngtimer” exhibition until 2 November 2025 Developed...

Three years after the original 296 GT3 debuted at Spa-Francorchamps, Ferrari has returned to the iconic Belgian circuit to unveil its next evolution: the 296 GT3 Evo. This isn’t just...

Porsche has once again proven its relentless commitment to pushing the limits of automotive performance, regardless of powertrain. In a remarkable display of engineering versatility, two very different models —...

Lamborghini has been the epitome of incomparable style, outstanding performance, exclusivity and innovation since 1963. Its limited-edition series are the ultimate embodiment of its creative and technical prowess. They are...

The Praga Bohema is a $1.5 million, track-focused hypercar designed to rewrite the rulebook on what a road-legal performance machine can be. The performance figures are impressive—0–62 mph in 3.3...

The CONCEPT AMG GT XX is a pioneering technology program that offers an impressive look into a forthcoming four-door series-production sports car from Mercedes‑AMG. With three axial flux motors and...

Features Stories & Member-Only Content

Behind-the-Scenes Coverage, In-Depth Stories and Premium Editorials for Our Members

Koenigsegg proudly unveils Sadair’s Spear—a track-focused, road-legal masterpiece that redefines performance benchmarks. With more power, less weight, cutting-edge aerodynamics, and bespoke engineering throughout, this limited-edition hypercar pushes the boundaries of...

The Monterey Motorsports Festival is delighted to announce the Peralta S designed by Fabrizio Giugiaro will make its US debut at the show on August 16, 2025. As undoubtedly the...

In this drag race showdown, Mat Watson and his team from carwow will be pitting two hypercars, a Ferrari Daytona SP3, and a Pagani Huayra Roadster BC, to see which...

The Mercedes-AMG ONE is a rare, plug-in hybrid hypercar integrating Formula One technology into a road-legal platform. First revealed in concept form at the 2017 Frankfurt Motor Show by Lewis...

The Lamborghini SC63 is back on track this weekend for the third round of the 2024 IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Championship, taking on the legendary and scenic Watkins Glen International in...

Bugatti continues to redefine luxury and performance with its latest innovation—the Bugatti Tourbillon configurator. Rooted in the legacy of Ettore Bugatti’s vision for individuality and pioneering spirit, this new chapter...

The Ferrari Daytona SP3 has been featured in an episode of Jay Leno’s Garage on YouTube. The SP3 is the latest addition to Ferrari’s Icona series, a lineup that pays homage...

The Ferrari 12Cilindri carries the weight of a storied legacy rooted in the brand’s long history of V12-powered grand tourers. Ferrari’s relationship with the V12 engine dates back to 1947, when...

You don’t have to be a car enthusiast to appreciate a car beyond its monetary value. Almost anyone who owns an automobile considers these wheeled motor vehicles prized possessions that...

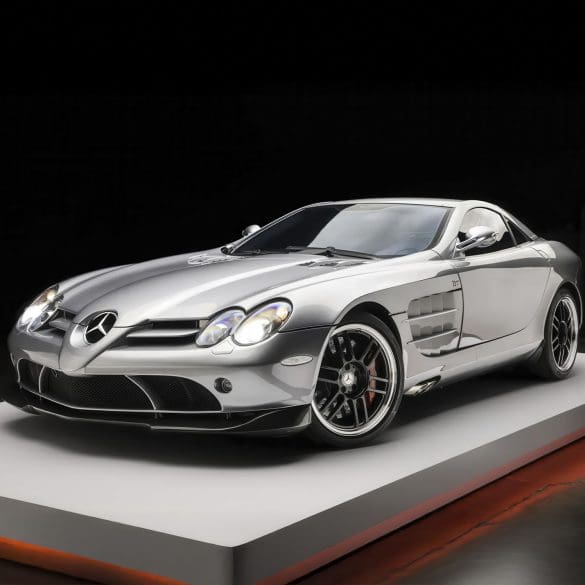

This 2007 Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren is a limited-production 722 Edition that is one of a claimed 150 coupes built over a two-year production run as an homage to Sir Stirling...

MANSORY Unveils the “Initiate” – A Striking Hybrid Evolution of the Lamborghini Revuelto In the exclusive world of super sports cars, few names command the same respect and reverence as...

British advanced automotive engineering and design company, Gordon Murray Group (GMG), has announced that its new ‘Special Vehicles’ division will reveal its first two models on 15 August at The...

In a recent video from CarExpert on YouTube, we are treated to a thrilling drag race between two expensive and high-end performance machines: a McLaren Senna and Ferrari 812 Competizione....

This 2019 McLaren Senna, listed on Collecting Cars, is number 303 of just 500 units built as part of McLaren’s Ultimate Series. With only 576 kilometers (398 miles) recorded, it’s...

McLaren Automotive and McLaren Racing have joined forces to unveil Project: Endurance – an extraordinary customer partnership programme offering a rare opportunity to experience the thrill of piloting a true...

Our Most Popular Research Hubs

Model Guides, Videos & Cars for Sale. We Have It All If You're a Car Nut